Nick Bentley

Today

Interviews: Inside the Privateer Pits - Fort William World Cup DH 2024

Interviews: Inside the Privateer Pits - Fort William World Cup DH 2024

We hear from the privateers of Fort William about what they thought of the new Privateer Pits along with Ruaridh Cunningham, who is the Director of Gravity Sport at Warner Brothers Discovery.

Sarah Moore

Today

Frameworks DH Bikes Stolen in Milton Keynes, UK

Frameworks DH Bikes Stolen in Milton Keynes, UK

Asa Vermette, Angel Suarez and Neko Mulally's Frameworks race bikes were stolen from their van in Milton Keynes, UK.

Nick Bentley

Today

Interview: Data Acquisition & Developing Future Champions with Nick Lester - Team Manager of the Muc-Off Young Guns

Interview: Data Acquisition & Developing Future Champions with Nick Lester - Team Manager of the Muc-Off Young Guns

Muc-Off Young Guns rider Heather Wilson took the win at her first ever World Cup.

Matt Beer

Today

Review: EXT Aria Air Shock

Review: EXT Aria Air Shock

There were a few hiccups, but by the end of testing the Aria delivered excellent mid-stroke support and bottom out resistance.

Kona Bikes

Today

Video: Whistler Hype Edit with Peter Wojnar & Matt Tongue in 'Lost Property'

Video: Whistler Hype Edit with Peter Wojnar & Matt Tongue in 'Lost Property'

Just one week left until Whismas!

Sarah Moore

Today

Video: Matt Jones Builds A Huge Ramp & Jumps Over His House

Video: Matt Jones Builds A Huge Ramp & Jumps Over His House

"Even as a kid I dreamed of jumping over a house and now it's time to do it for real."

Nick Bentley

Today

Interview: Adam Brayton on 100 World Cup DH Starts - Fort William World Cup DH 2024

Interview: Adam Brayton on 100 World Cup DH Starts - Fort William World Cup DH 2024

There aren't very many riders out there who have raced in 100 World Cups, and this weekend at Fort William, Adam Brayton joined that elite club.

Details Announced for Hotlaps MTB Event

Details Announced for Hotlaps MTB Event

Enduro, dual slalom, jump jam, and more.

Outside Online

Today

The new rate will go into effect starting today for new customers and at the next pay cycle after June 6 for current customers.

Dario DiGiulio

Today

First Look: The Rotwild R.EXC is a Race-Focused eMTB With a 820 Wh Battery

First Look: The Rotwild R.EXC is a Race-Focused eMTB With a 820 Wh Battery

The R.EXC has a 820 Wh battery and uses a Shimano EP801 motor.

Ed Spratt

May 7, 2024

Must Watch: Wild Scenes in the Sleeper Shreddit from the Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Must Watch: Wild Scenes in the Sleeper Shreddit from the Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Sleeper are back to start the 2024 season with another incredible race shreddit.

COMMENCAL BIKES & SKIS

Today

Video: Commencal Shares the Stoke for Opening Day at the Whistler Bike Park

Video: Commencal Shares the Stoke for Opening Day at the Whistler Bike Park

Only a week to go before A-Line laps are back on!

Holly Duncan

Today

Trailforks Trail of the Month: Deliverance - Squamish, BC

Trailforks Trail of the Month: Deliverance - Squamish, BC

This old-school steep and deep trail, recently got a new-school makeover.

ECHOS Communications

Today

Chris King Introduces Generation 4 Hub System

Chris King Introduces Generation 4 Hub System

The hubs have a new driver / axle system, and more universal parts.

Sarah Moore

May 6, 2024

Brett Rheeder Announces He’s Sold Title MTB, Intends to Start New Brand

Brett Rheeder Announces He’s Sold Title MTB, Intends to Start New Brand

We look forward to seeing what Rheeder cooks up next.

WeAreOne Composites

May 6, 2024

Video: We Are One Momentum Project with Mark Wallace & Jon Mozell - Episode 2

Video: We Are One Momentum Project with Mark Wallace & Jon Mozell - Episode 2

The final pre-season test camp before Fort William with the We Are One crew.

Jessie-May Morgan

May 6, 2024

4 Tech Takeaways From the Fort William DH World Cup

4 Tech Takeaways From the Fort William DH World Cup

We take a moment to reflect on a track that is faster than ever, and the bikes and technology being deployed to help riders beat the clock.

Dario DiGiulio

May 6, 2024

Review: Starling MegaMurmur - The Big Bird

Review: Starling MegaMurmur - The Big Bird

With 165mm of rear travel, this British-made beast is meant to handle the fastest and gnarliest terrain around.

TEBP

May 6, 2024

Day 2 Randoms: Bike Festival Riva 2024

Day 2 Randoms: Bike Festival Riva 2024

There are some seriously wild designs in this roundup from Riva.

Wyn Masters

May 6, 2024

Video: WynTV Finals Day - Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Video: WynTV Finals Day - Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Wyn hits the pits to catch all the stories after an epic round one of the 2024 DH World Cup at Fort William!

Official Crankworx

May 6, 2024

Crankworx Cairns Announces Preliminary Rider Lists, Course Updates & More

Crankworx Cairns Announces Preliminary Rider Lists, Course Updates & More

The Crankworx World Tour heads to Cairns next from May 22-26.

Pinkbike Originals

May 6, 2024

Video: Spectacular Racing in Fort William - Story Of The Race with Ben Cathro

Video: Spectacular Racing in Fort William - Story Of The Race with Ben Cathro

Enjoy the soothing tones of the wonderful Ben Cathro as we kick off the 2024 season coverage.

Outside Online

May 6, 2024

Of the 15 trail bikes we tested last year, these impressed us the most.

Mountain Biking BC

May 6, 2024

Opening Days Announced for 7 of British Columbia's Bike Parks

Opening Days Announced for 7 of British Columbia's Bike Parks

The summer 2024 season is about to get started.

Ed Spratt

May 6, 2024

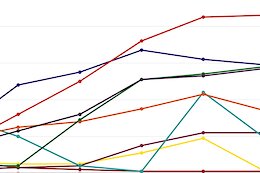

Elite & Junior Race Analysis from the Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Elite & Junior Race Analysis from the Fort William DH World Cup 2024

A deep dive into the stats and splits from round one of the 2024 Downhill World Cup series.

Ed Spratt

May 6, 2024

Finals Photo Epic: Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Finals Photo Epic: Fort William DH World Cup 2024

The legendary Fort William course delivered more racing moments to remember.

Pinkbike Staff

May 6, 2024

Fantasy DH League Results: Who Won the First Round - Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Fantasy DH League Results: Who Won the First Round - Fort William DH World Cup 2024

The results are in for the first round of Pinkbike's DH Fantasy League, presented by the good people at Five Ten.

RideWrap HQ

May 6, 2024

RideWrap Launches Protection Film Made from Recycled Materials

RideWrap Launches Protection Film Made from Recycled Materials

The bicycle-specific protection film is made from 77% recycled materials with embedded superhydrophobic ceramic and self-healing properties.

Ed Spratt

May 6, 2024

Video: Christian Arehart's World First MTB Quad Flip

Video: Christian Arehart's World First MTB Quad Flip

A huge new world first from Christian Arehart.

Archive Navigator

2024 Advertiser List

Brands

Bikes

- Trek

- Specialized

- Devinci

- Rocky Mountain

- Giant Bikes

- Scott

- Kona

- Norco

- Commencal

- NS Bikes

- Santa Cruz

- Yeti

- YT Industries

- Polygon Bikes

- Cube

- Radon Bikes

- Marin

- Guerrilla Gravity

- RSD Bikes

- Propain Bikes

- DMR Bikes

- Canyon

- PRIME Bicycles

- Pivot Cycles

- Hybridizer Bikes

Components

- SRAM

- Shimano

- Race Face

- Industry Nine

- SDG

- Deity

- Hunt Wheels

- One Up Components

- KS

- Rotor Bike Components

- Stan’s NoTubes

- Reverse Components

- RideWrap

- PROLOGO

- Yoshimura Cycling

- TRP Cycling

- Galfer USA

- Bikeyoke

- e*thirteen

- Geo Handguards

Suspension

Tires

Accessories

Coaching and Education

Online Retailers

Resorts/Riding

- Trestle Bike Park

- Bike Parks BC

- Fernie

- Crested Butte

- Big White

- Saalbach Hinterglemm

- Whitefish Mountain Resort

- Visit Tucson

- Monument Trails

- Mountain Bike Park City

Final Randoms: Bike Festival Riva 2024

Final Randoms: Bike Festival Riva 2024