Tom Booker

Today

Video: Reece Potter, Conor Macfarlane & Friends Bring the Gnar to Queenstown in 'Tour De Yeah, Nah'

Video: Reece Potter, Conor Macfarlane & Friends Bring the Gnar to Queenstown in 'Tour De Yeah, Nah'

Serious gnar inspired by the Canadian event.

Wyn Masters

Today

Video: WynTV from the 2024 Sea Otter Classic Slalom

Video: WynTV from the 2024 Sea Otter Classic Slalom

Wyn hits the Sea Otter classic Dual slalom, the unofficial world championships of slalom for 2024 to see what went down!

Dario DiGiulio

Today

Downhill Bikes of Sea Otter - Part 2

Downhill Bikes of Sea Otter - Part 2

Five more downhill machines, most built for speed and one built for mega hucking.

Outside Online

Today

The iconic history of freeride will be available to own from April 23rd.

Dakine

Today

Dakine Announces The Universal Pickup Pad

Dakine Announces The Universal Pickup Pad

The small size secures five bikes, while the large size accommodates up to seven.

Izzy Lidsky

Today

3 Initiatives at Sea Otter Pushing for a More Inclusive Bike Industry

3 Initiatives at Sea Otter Pushing for a More Inclusive Bike Industry

New bike tech and exciting race results weren't the only things making a splash in the industry at Sea Otter Classic.

Dario DiGiulio

Today

Dario's Final Sea Otter Randoms

Dario's Final Sea Otter Randoms

"I have become the otter...I know not of bicycles or their constituent parts, I know only of clams, rocks, and water."

Matt Beer

Today

A Deeper Look At The Latest Trinity MTB Gravity Project

A Deeper Look At The Latest Trinity MTB Gravity Project

Mic Williams explains how he has applied the WRP Centre Hub to a custom built gearbox.

Outside Online

Today

Unable to race at Sea Otter due to injury, pro off-road cyclist Caroline Dezendorf instead became a judge — of cappuccino, cold brew, and latte art.

bikebigwhite

Today

RAW Video: Bas Van Steenbergen Rides Big White in 'Bas Knows Best'

RAW Video: Bas Van Steenbergen Rides Big White in 'Bas Knows Best'

Bike park season is coming!

Sarah Moore

Apr 22, 2024

5 Things We Learned from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

5 Things We Learned from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

Christopher Blevins just beat Tom Pidcock's unofficial record for number of passes in a World Cup race, the most hotly contested Olympic spots, and more.

Seb Stott

Apr 23, 2024

First Ride: All-New Saracen Myst

First Ride: All-New Saracen Myst

Saracen's redesigned race bike is now available to buy

Izzy Lidsky

Apr 22, 2024

Hidden Treasures From the 'For Sale' Fence at Sea Otter 2024

Hidden Treasures From the 'For Sale' Fence at Sea Otter 2024

It's like the Pinkbike BuySell, but in real life.

Izzy Lidsky

Today

Photo Story: 'Sea Otter Dual Slalom For Dummies' - A Play by Play of the Race From a First Time Watcher

Photo Story: 'Sea Otter Dual Slalom For Dummies' - A Play by Play of the Race From a First Time Watcher

Dual Slalom as told by someone who had no idea what they were looking at.

sarisnews

Today

Saris Announces New Tailgate Pad

Saris Announces New Tailgate Pad

The Small (up to five bike positions) will retail for $219 and the Large (up to six bike positions) is available for $229.

Ravanel-MTB

Today

Commencal Les Orres Shows Off 2024 Team Kit & Bike

Commencal Les Orres Shows Off 2024 Team Kit & Bike

The team will be reunited soon in Fort William.

Jakub Vencl

Apr 22, 2024

Must Watch: Heavy Moves from Jakub Vencl in 'One Nine One'

Must Watch: Heavy Moves from Jakub Vencl in 'One Nine One'

Heavy moves, heavy music, heavy industry.

Brian Park

Apr 22, 2024

Brian's Randoms from Sea Otter 2024

Brian's Randoms from Sea Otter 2024

The sun was out, and there was SO MUCH interesting new bike tech on display.

Ed Spratt

Apr 22, 2024

XCO Photo Epic: Araxá XC World Cup 2024

XCO Photo Epic: Araxá XC World Cup 2024

Another weekend of racing in Brazil brought more incredible battles and wild fans for the second round of the 2024 series.

Dario DiGiulio

Apr 22, 2024

First Look: Deity Releases New Stems, Grips, & Pedals

First Look: Deity Releases New Stems, Grips, & Pedals

Flat Trak, Supervillain, Megattack, and Copperhead all hit the lineup this year.

Izzy Lidsky

Apr 22, 2024

Photo Report: Fast & Loose at the 2024 Sea Otter Dual Slalom

Photo Report: Fast & Loose at the 2024 Sea Otter Dual Slalom

Sea Otter's fan favourite event delivered the perfect Saturday afternoon entertainment.

Ed Spratt

Apr 21, 2024

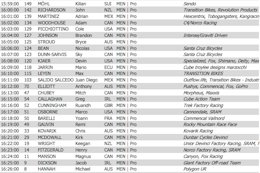

![[UPDATED] Final Elite XC Results & Overall Sta](https://ep1.pinkbike.org/p2pb20769079/p2pb20769079.jpg) [UPDATED] Final Elite XC Results & Overall Standings from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

[UPDATED] Final Elite XC Results & Overall Standings from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

The results are in from two amazing races in Brazil.

Ed Spratt

Apr 22, 2024

Results: Downhill - Sea Otter 2024

Results: Downhill - Sea Otter 2024

The results are in from the Downhill at Sea Otter 2024.

Magnus Manson

Apr 22, 2024

Video: Rhys Verner's Test Laps on the New Dreadnought

Video: Rhys Verner's Test Laps on the New Dreadnought

Rhys Verner get up to speed with the Dreadnought V2 on wet and soggy trails.

Ed Spratt

Apr 22, 2024

Video: Official Highlights from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

Video: Official Highlights from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

Catch up on all the action from the action-packed second stop of the 2024 XC World Cup series.

Ed Spratt

Apr 20, 2024

![[UPDATED] U23 XCO Results & Overall Standings](https://ep1.pinkbike.org/p2pb26491128/p2pb26491128.jpg) [UPDATED] U23 XCO Results & Overall Standings from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

[UPDATED] U23 XCO Results & Overall Standings from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

The U23 results are in from round two.

Ed Spratt

Apr 22, 2024

Video: Official Highlights from the Fuego XL at the 2024 Sea Otter Classic

Video: Official Highlights from the Fuego XL at the 2024 Sea Otter Classic

Catch up on the racing with the full extended highlights from 2024’s Sea Otter Classic presented by Continental Fuego XL.

Scott Secco

Apr 22, 2024

Movies For Your Monday - Steve Peat, Brendan Howey, Vaea Verbeeck, Kye Petersen, & More

Movies For Your Monday - Steve Peat, Brendan Howey, Vaea Verbeeck, Kye Petersen, & More

Kick-start your week with 20 great edits.

Archive Navigator

2024 Advertiser List

Brands

Bikes

- Trek

- Specialized

- Devinci

- Rocky Mountain

- Giant Bikes

- Scott

- Kona

- Norco

- Commencal

- NS Bikes

- Santa Cruz

- Yeti

- YT Industries

- Polygon Bikes

- Cube

- Radon Bikes

- Marin

- Guerrilla Gravity

- RSD Bikes

- Propain Bikes

- DMR Bikes

- Canyon

- PRIME Bicycles

- Pivot Cycles

Components

- SRAM

- Shimano

- Race Face

- Industry Nine

- SDG

- Deity

- Hunt Wheels

- One Up Components

- KS

- Rotor Bike Components

- Stan’s NoTubes

- Reverse Components

- RideWrap

- PROLOGO

- Yoshimura Cycling

- TRP Cycling

- Galfer USA

- Bikeyoke

- e*thirteen

- Geo Handguards

Suspension

Tires

Accessories

Coaching and Education

Online Retailers

Resorts/Riding

- Trestle Bike Park

- Bike Parks BC

- Fernie

- Crested Butte

- Big White

- Saalbach Hinterglemm

- Whitefish Mountain Resort

- Visit Tucson

- Monument Trails

- Mountain Bike Park City

Downhill Bikes of Sea Otter - Part 1

Downhill Bikes of Sea Otter - Part 1  What's New for the Kids at Sea Otter 2024

What's New for the Kids at Sea Otter 2024