Pinkbike Originals

Today

Video: The Brutal Opening Round of 2024 - Inside the Tape with Ben Cathro

Video: The Brutal Opening Round of 2024 - Inside the Tape with Ben Cathro

Downhill racing is back, and Fort William is faster than ever.

Ed Spratt

Today

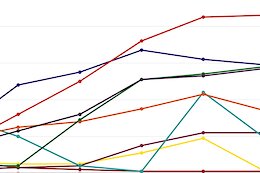

Qualifying & Semi-Finals Analysis from the Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Qualifying & Semi-Finals Analysis from the Fort William DH World Cup 2024

We have taken a deep dive into the splits to look at the important numbers from qualifying and Semi-Finals at Fort William.

Ed Spratt

Today

Semi-Final Results from the Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Semi-Final Results from the Fort William DH World Cup 2024

The results are in from the first semi-finals of the 2024 season.

Ed Spratt

Today

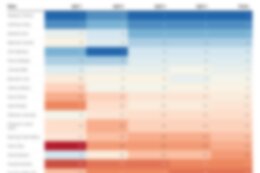

Junior Qualifying Analysis from the Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Junior Qualifying Analysis from the Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Split data and race stats from the Junior Qualifying at Fort William.

Ed Spratt

Today

Video: Trackside Highlights from the Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Video: Trackside Highlights from the Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Official highlights from qualifying and semi-finals in Fort William.

Jessie-May Morgan

Today

15 Privateer Bikes at Fort William World Cup 2024

15 Privateer Bikes at Fort William World Cup 2024

The workhorses of DH World Cup privateers

Ed Spratt

Today

Junior Qualifying Results from the Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Junior Qualifying Results from the Fort William DH World Cup 2024

The results are in from the Junior qualifying at Fort William.

Ed Spratt

Today

Elite Qualifying Results from the Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Elite Qualifying Results from the Fort William DH World Cup 2024

The elite qualifying results are in with the decision made on who progresses to the semi-finals.

Jessie-May Morgan

Today

Bike Check: Dakotah Norton's Prototype Mondraker Summum at Fort William World Cup

Bike Check: Dakotah Norton's Prototype Mondraker Summum at Fort William World Cup

Holy-high-rise handlebars, completed with pannier rack mounts.

Ed Spratt

Today

Practice Photo Epic: Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Practice Photo Epic: Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Downhill World Cup racing is back as Fort William returns as the series' opening round for the first time since 2013.

Ed Spratt

Today

Video: Practice Day Action from the Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Video: Practice Day Action from the Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Incredible conditions for the first day of riding at Fort William.

SDG Components

May 3, 2024

MUST WATCH: Brage Vestavik & Nico Vink in 'Sandscape Eternal'

MUST WATCH: Brage Vestavik & Nico Vink in 'Sandscape Eternal'

18 minutes of raw, brutal freeride from Brage and Nico Vink in one of the driest places on earth. So punishing, so good.

Sarah Moore

May 3, 2024

Paul Bas Walks Half Marathon 8 Years After Being Paralyzed at Red Bull Rampage

Paul Bas Walks Half Marathon 8 Years After Being Paralyzed at Red Bull Rampage

Incredible to see Paul Basagoitia being able to walk 21km (13.1 miles).

Jessie-May Morgan

May 3, 2024

Bike Check: Greg Minnaar's Norco Prototype DH Bike at Fort William World Cup

Bike Check: Greg Minnaar's Norco Prototype DH Bike at Fort William World Cup

After 16 years with the Santa Cruz Syndicate, the GOAT is on a Norco for 2024

Mike Kazimer

May 3, 2024

Pinkbike Poll: Hip Pack, Vest, or Backpack?

Pinkbike Poll: Hip Pack, Vest, or Backpack?

Or maybe you fill your cargo pant pockets with snacks and tools?

Pinkbike Originals

May 3, 2024

Video: Fort William DH World Cup Course Preview 2024 (With A Twist)

Video: Fort William DH World Cup Course Preview 2024 (With A Twist)

Ben Cathro commentates as first-year Junior Heather Wilson from the Muc-Off Young Guns team hits the Fort William World Cup DH track.

Ed Spratt

May 2, 2024

![[UPDATED] Video Round Up: Fort William DH World Cu](https://ep1.pinkbike.org/p2pb26593782/p2pb26593782.jpg) [UPDATED] Video Round Up: Fort William DH World Cup 2024

[UPDATED] Video Round Up: Fort William DH World Cup 2024

All the action so far from this week's racing at Fort William.

Outside Online

May 3, 2024

More than two decades after a crash left him paralyzed, Tarek Rasouli rekindled his love of off-road riding with the help of an innovative handcycle.

Sarah Moore

May 3, 2024

Video Round Up: Course Previews from Ronan Dunne, Laurie Greenland, & More - Fort William World Cup DH 2024

Video Round Up: Course Previews from Ronan Dunne, Laurie Greenland, & More - Fort William World Cup DH 2024

All the videos from the Bill.

Ed Spratt

May 3, 2024

Timed Training Results: Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Timed Training Results: Fort William DH World Cup 2024

The most important results of the weekend are in from Fort William.

Pinkbike Originals

May 3, 2024

Video: Friday Fails #320

Video: Friday Fails #320

Back in action for some Friday Fails featuring some classic OTB's!

Ed Spratt

May 3, 2024

Bike Check: Oisin O'Callaghan's New YT Tues Race Bike - Fort William World Cup DH 2024

Bike Check: Oisin O'Callaghan's New YT Tues Race Bike - Fort William World Cup DH 2024

A brand new frame and free reign on parts spec make for a truly unique ride.

Henry Quinney

May 3, 2024

Spotted: Speculating on the New Lapierre Downhill Bike - Fort William World Cup DH 2024

Spotted: Speculating on the New Lapierre Downhill Bike - Fort William World Cup DH 2024

Antoine Rogge takes to Aonach Mòr on a high-pivot prototype from Lapierre

Jessie-May Morgan

May 3, 2024

Even More Tech Randoms: Fort William World Cup DH 2024

Even More Tech Randoms: Fort William World Cup DH 2024

The Fort William World Cup keeps on serving up new tech.

Jessie-May Morgan

May 3, 2024

First Look: Vittoria's New Mostro Enduro Race Tire

First Look: Vittoria's New Mostro Enduro Race Tire

Vittoria roll out a new gravity tire that sits between the Mota and the Mazza.

Wyn Masters

May 3, 2024

Video: WynTV Track Walk - Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Video: WynTV Track Walk - Fort William DH World Cup 2024

Wyn hits the track walk at Fort William to see how everyone is feeling coming into the big round one showdown this weekend.

ForbiddenBike

May 3, 2024

Video: Marcel Hunt & Friends At the Bike Ranch In Kamloops for 'Kids Line'

Video: Marcel Hunt & Friends At the Bike Ranch In Kamloops for 'Kids Line'

A good ol’ time in the air.

COMMENCAL BIKES & SKIS

May 2, 2024

Video: Billy Meaclem Styles it Out on Perfectly Sculpted Handbuilt Jumps in 'Payday'

Video: Billy Meaclem Styles it Out on Perfectly Sculpted Handbuilt Jumps in 'Payday'

Watch Billy Meaclem style it out on handmade secret trails in the middle of a forest in NZ!

Pinkbike Staff

Apr 30, 2024

LAST CHANCE: Build Your Team Ahead of Round 1 - Fort William World Cup DH 2024

LAST CHANCE: Build Your Team Ahead of Round 1 - Fort William World Cup DH 2024

We're heading into the first round of Pinkbike's DH Fantasy League, presented by the good people at Five Ten.

Rémy Métailler

May 2, 2024

Video: Dirt Surfing in California with Remy Metailler & Drew Palmer Leger

Video: Dirt Surfing in California with Remy Metailler & Drew Palmer Leger

Dirt doesn't get much better than this.

Archive Navigator

2024 Advertiser List

Brands

Bikes

- Trek

- Specialized

- Devinci

- Rocky Mountain

- Giant Bikes

- Scott

- Kona

- Norco

- Commencal

- NS Bikes

- Santa Cruz

- Yeti

- YT Industries

- Polygon Bikes

- Cube

- Radon Bikes

- Marin

- Guerrilla Gravity

- RSD Bikes

- Propain Bikes

- DMR Bikes

- Canyon

- PRIME Bicycles

- Pivot Cycles

- Hybridizer Bikes

Components

- SRAM

- Shimano

- Race Face

- Industry Nine

- SDG

- Deity

- Hunt Wheels

- One Up Components

- KS

- Rotor Bike Components

- Stan’s NoTubes

- Reverse Components

- RideWrap

- PROLOGO

- Yoshimura Cycling

- TRP Cycling

- Galfer USA

- Bikeyoke

- e*thirteen

- Geo Handguards

Suspension

Tires

Accessories

Coaching and Education

Online Retailers

Resorts/Riding

- Trestle Bike Park

- Bike Parks BC

- Fernie

- Crested Butte

- Big White

- Saalbach Hinterglemm

- Whitefish Mountain Resort

- Visit Tucson

- Monument Trails

- Mountain Bike Park City