Sarah Moore

Today

Podcast: Lael Wilcox Aims to Circumnavigate the Planet in Just 110 Days

Podcast: Lael Wilcox Aims to Circumnavigate the Planet in Just 110 Days

To get a place in the Guinness Book of World Records, Lael Wilcox will need to cover the 29,600km in less than 124 days and 11 hours.

Mike Kazimer

Today

Vivo Cycling Previews All-Aluminum 12-Speed Derailleur

Vivo Cycling Previews All-Aluminum 12-Speed Derailleur

Fingers crossed there's a purple ano version in the works.

Sarah Moore

Today

The Ultimate Recap of Sea Otter 2024

The Ultimate Recap of Sea Otter 2024

Here's everything you could ever want to know about Sea Otter 2024.

Henry Quinney

Today

The Pinkbike Podcast: Is World Cup XC Actually Worth Watching?

The Pinkbike Podcast: Is World Cup XC Actually Worth Watching?

Our resident XC expert, Sarah Moore, a former World Cup racer, explains to Henry why XC has never been so good.

Tom Booker

Today

Video: Reece Potter, Conor Macfarlane & Friends Bring the Gnar to Queenstown in 'Tour De Yeah, Nah'

Video: Reece Potter, Conor Macfarlane & Friends Bring the Gnar to Queenstown in 'Tour De Yeah, Nah'

Serious gnar inspired by the Canadian event.

Outside Online

Today

Giant Manufacturing says Stages owed it $14 million for production.

Cycles Devinci

Today

Devinci Announces All-New E-Troy Lite & Yoann Barelli Shreds It

Devinci Announces All-New E-Troy Lite & Yoann Barelli Shreds It

The Troy has 150mm of rear travel, mixed wheels, and a Bosch Performance Line SX 55Nm motor with a 400Wh battery.

Official Crankworx

Today

Photographers: Applications Are Now Open for the Crankworx Whistler Deep Summer Photo Challenge

Photographers: Applications Are Now Open for the Crankworx Whistler Deep Summer Photo Challenge

For the first time, Crankworx will be taking applications from photographers who want to take part in the Deep Summer Photo Challenge.

ForbiddenBike

Today

Video: Emmy Lan's Off Season Training on Vancouver Island

Video: Emmy Lan's Off Season Training on Vancouver Island

Emmy Lan, the reigning U21 Enduro World Series champion, takes on the off-season in her home of Comox, BC.

Pinkbike Staff

Mar 18, 2024

Pinkbike's DH Fantasy League: Get Your Team On The Line - Fort William is in 10 DAYS!

Pinkbike's DH Fantasy League: Get Your Team On The Line - Fort William is in 10 DAYS!

Now with dynamic rider pricing, this year's fantasy league will be more interesting than ever, and there are some great prizes up for grabs too.

Wyn Masters

Apr 23, 2024

Video: WynTV from the 2024 Sea Otter Classic Slalom

Video: WynTV from the 2024 Sea Otter Classic Slalom

Wyn hits the Sea Otter classic Dual slalom, the unofficial world championships of slalom for 2024 to see what went down!

Dario DiGiulio

Apr 23, 2024

Downhill Bikes of Sea Otter - Part 2

Downhill Bikes of Sea Otter - Part 2

Five more downhill machines, most built for speed and one built for mega hucking.

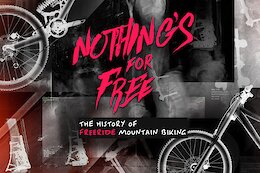

Outside Online

Apr 23, 2024

The iconic history of freeride will be available to own from April 23rd.

Dakine

Apr 23, 2024

Dakine Announces The Universal Pickup Pad

Dakine Announces The Universal Pickup Pad

The small size secures five bikes, while the large size accommodates up to seven.

Izzy Lidsky

Apr 23, 2024

3 Initiatives at Sea Otter Pushing for a More Inclusive Bike Industry

3 Initiatives at Sea Otter Pushing for a More Inclusive Bike Industry

New bike tech and exciting race results weren't the only things making a splash in the industry at Sea Otter Classic.

Dario DiGiulio

Apr 23, 2024

Dario's Final Sea Otter Randoms

Dario's Final Sea Otter Randoms

"I have become the otter...I know not of bicycles or their constituent parts, I know only of clams, rocks, and water."

Matt Beer

Apr 23, 2024

A Deeper Look At The Latest Trinity MTB Gravity Project

A Deeper Look At The Latest Trinity MTB Gravity Project

Mic Williams explains how he has applied the WRP Centre Hub to a custom built gearbox.

Outside Online

Apr 23, 2024

Unable to race at Sea Otter due to injury, pro off-road cyclist Caroline Dezendorf instead became a judge — of cappuccino, cold brew, and latte art.

bikebigwhite

Apr 23, 2024

RAW Video: Bas Van Steenbergen Rides Big White in 'Bas Knows Best'

RAW Video: Bas Van Steenbergen Rides Big White in 'Bas Knows Best'

Bike park season is coming!

Sarah Moore

Apr 22, 2024

5 Things We Learned from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

5 Things We Learned from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

Christopher Blevins just beat Tom Pidcock's unofficial record for number of passes in a World Cup race, the most hotly contested Olympic spots, and more.

Seb Stott

Apr 23, 2024

First Ride: All-New Saracen Myst

First Ride: All-New Saracen Myst

Saracen's redesigned race bike is now available to buy

Izzy Lidsky

Apr 22, 2024

Hidden Treasures From the 'For Sale' Fence at Sea Otter 2024

Hidden Treasures From the 'For Sale' Fence at Sea Otter 2024

It's like the Pinkbike BuySell, but in real life.

Izzy Lidsky

Apr 23, 2024

Photo Story: 'Sea Otter Dual Slalom For Dummies' - A Play by Play of the Race From a First Time Watcher

Photo Story: 'Sea Otter Dual Slalom For Dummies' - A Play by Play of the Race From a First Time Watcher

Dual Slalom as told by someone who had no idea what they were looking at.

sarisnews

Apr 23, 2024

Saris Announces New Tailgate Pad

Saris Announces New Tailgate Pad

The Small (up to five bike positions) will retail for $219 and the Large (up to six bike positions) is available for $229.

Ravanel-MTB

Apr 23, 2024

Commencal Les Orres Shows Off 2024 Team Kit & Bike

Commencal Les Orres Shows Off 2024 Team Kit & Bike

The team will be reunited soon in Fort William.

Jakub Vencl

Apr 22, 2024

Must Watch: Heavy Moves from Jakub Vencl in 'One Nine One'

Must Watch: Heavy Moves from Jakub Vencl in 'One Nine One'

Heavy moves, heavy music, heavy industry.

Brian Park

Apr 22, 2024

Brian's Randoms from Sea Otter 2024

Brian's Randoms from Sea Otter 2024

The sun was out, and there was SO MUCH interesting new bike tech on display.

Ed Spratt

Apr 22, 2024

XCO Photo Epic: Araxá XC World Cup 2024

XCO Photo Epic: Araxá XC World Cup 2024

Another weekend of racing in Brazil brought more incredible battles and wild fans for the second round of the 2024 series.

Dario DiGiulio

Apr 22, 2024

First Look: Deity Releases New Stems, Grips, & Pedals

First Look: Deity Releases New Stems, Grips, & Pedals

Flat Trak, Supervillain, Megattack, and Copperhead all hit the lineup this year.

Archive Navigator

2024 Advertiser List

Brands

Bikes

- Trek

- Specialized

- Devinci

- Rocky Mountain

- Giant Bikes

- Scott

- Kona

- Norco

- Commencal

- NS Bikes

- Santa Cruz

- Yeti

- YT Industries

- Polygon Bikes

- Cube

- Radon Bikes

- Marin

- Guerrilla Gravity

- RSD Bikes

- Propain Bikes

- DMR Bikes

- Canyon

- PRIME Bicycles

- Pivot Cycles

Components

- SRAM

- Shimano

- Race Face

- Industry Nine

- SDG

- Deity

- Hunt Wheels

- One Up Components

- KS

- Rotor Bike Components

- Stan’s NoTubes

- Reverse Components

- RideWrap

- PROLOGO

- Yoshimura Cycling

- TRP Cycling

- Galfer USA

- Bikeyoke

- e*thirteen

- Geo Handguards

Suspension

Tires

Accessories

Coaching and Education

Online Retailers

Resorts/Riding

- Trestle Bike Park

- Bike Parks BC

- Fernie

- Crested Butte

- Big White

- Saalbach Hinterglemm

- Whitefish Mountain Resort

- Visit Tucson

- Monument Trails

- Mountain Bike Park City

Downhill Bikes of Sea Otter - Part 1

Downhill Bikes of Sea Otter - Part 1