Sarah Moore

Today

5 Things We Learned from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

5 Things We Learned from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

Christopher Blevins just beat Tom Pidcock's unofficial record for number of passes in a World Cup race, the most hotly contested Olympic spots, and more.

Izzy Lidsky

Today

Hidden Treasures From the 'For Sale' Fence at Sea Otter 2024

Hidden Treasures From the 'For Sale' Fence at Sea Otter 2024

It's like the Pinkbike BuySell, but in real life.

JakubVencl

Today

Must Watch: Heavy Moves from Jakub Vencl in 'One Nine One'

Must Watch: Heavy Moves from Jakub Vencl in 'One Nine One'

Heavy moves, heavy music, heavy industry.

Brian Park

Today

Brian's Randoms from Sea Otter 2024

Brian's Randoms from Sea Otter 2024

The sun was out, and there was SO MUCH interesting new bike tech on display.

Ed Spratt

Today

XCO Photo Epic: Araxá XC World Cup 2024

XCO Photo Epic: Araxá XC World Cup 2024

Another weekend of racing in Brazil brought more incredible battles and wild fans for the second round of the 2024 series.

Dario DiGiulio

Today

First Look: Deity Releases New Stems, Grips, & Pedals

First Look: Deity Releases New Stems, Grips, & Pedals

Flat Trak, Supervillain, Megattack, and Copperhead all hit the lineup this year.

Izzy Lidsky

Today

Photo Report: Fast & Loose at the 2024 Sea Otter Dual Slalom

Photo Report: Fast & Loose at the 2024 Sea Otter Dual Slalom

Sea Otter's fan favourite event delivered the perfect Saturday afternoon entertainment.

Ed Spratt

Apr 21, 2024

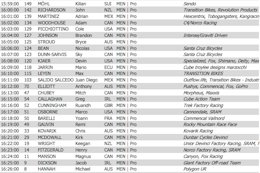

![[UPDATED] Final Elite XC Results & Overall Sta](https://ep1.pinkbike.org/p2pb20769079/p2pb20769079.jpg) [UPDATED] Final Elite XC Results & Overall Standings from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

[UPDATED] Final Elite XC Results & Overall Standings from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

The results are in from two amazing races in Brazil.

Ed Spratt

Today

Results: Downhill - Sea Otter 2024

Results: Downhill - Sea Otter 2024

The results are in from the Downhill at Sea Otter 2024.

Magnus Manson

Today

Video: Rhys Verner's Test Laps on the New Dreadnought

Video: Rhys Verner's Test Laps on the New Dreadnought

Rhys Verner get up to speed with the Dreadnought V2 on wet and soggy trails.

Ed Spratt

Today

Video: Official Highlights from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

Video: Official Highlights from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

Catch up on all the action from the action-packed second stop of the 2024 XC World Cup series.

Ed Spratt

Apr 20, 2024

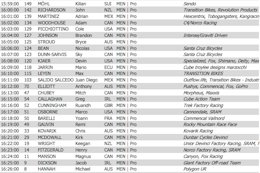

![[UPDATED] U23 XCO Results & Overall Standings](https://ep1.pinkbike.org/p2pb26491128/p2pb26491128.jpg) [UPDATED] U23 XCO Results & Overall Standings from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

[UPDATED] U23 XCO Results & Overall Standings from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

The U23 results are in from round two.

Ed Spratt

Today

Video: Official Highlights from the Fuego XL at the 2024 Sea Otter Classic

Video: Official Highlights from the Fuego XL at the 2024 Sea Otter Classic

Catch up on the racing with the full extended highlights from 2024’s Sea Otter Classic presented by Continental Fuego XL.

Scott Secco

Apr 22, 2024

Movies For Your Monday - Steve Peat, Brendan Howey, Vaea Verbeeck, Kye Petersen, & More

Movies For Your Monday - Steve Peat, Brendan Howey, Vaea Verbeeck, Kye Petersen, & More

Kick-start your week with 20 great edits.

Pinkbike Originals

Apr 21, 2024

Video: The Weird & Wonderful: How To Stand Out At Sea Otter With Ben Cathro

Video: The Weird & Wonderful: How To Stand Out At Sea Otter With Ben Cathro

Ben Cathro takes a lap of the venue to find his favourites.

Ed Spratt

Apr 21, 2024

XCC Photo Epic: Araxá XC World Cup 2024

XCC Photo Epic: Araxá XC World Cup 2024

The XC World Cup is back for another packed weekend as the always frantic XCC Short Track racing kicks off round two.

Dario DiGiulio

Apr 20, 2024

Randoms Round 3: Dario's Treasures

Randoms Round 3: Dario's Treasures

A bird, lots of suspension, various doodles, and much more.

Mike Kazimer

Apr 20, 2024

Even More Randoms - Sea Otter 2024

Even More Randoms - Sea Otter 2024

New shoes, forks, fancy kids bikes, tall bikes, and tire piles.

Ed Spratt

Apr 21, 2024

Joshua Dubau Injures Elbow After XCC Crash at the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

Joshua Dubau Injures Elbow After XCC Crash at the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

Joshua Dubau will not race in the second round of the XCO World Cup after dislocating and fracturing his elbow.

Ed Spratt

Apr 21, 2024

Replay: U23 XC Racing from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

Replay: U23 XC Racing from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

The U23 XC World Cup racing is back for another weekend of bar-to-bar action in Brazil.

Nikki Rohan

Apr 20, 2024

What's New in Women's MTB Apparel at Sea Otter 2024

What's New in Women's MTB Apparel at Sea Otter 2024

A selection of this year's women's specific mountain biking apparel.

Ed Spratt

Apr 21, 2024

Results: Dual Slalom - Sea Otter 2024

Results: Dual Slalom - Sea Otter 2024

The results are in from the Dual Slalom at Sea Otter 2024.

Ed Spratt

Apr 20, 2024

Elite XCC Results & Highlights from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

Elite XCC Results & Highlights from the Araxá XC World Cup 2024

The XCC results are in from Brazil.

Dario DiGiulio

Apr 20, 2024

Spotted: Frameworks Racing DH Bike with Electronic Fox Shock & Unreleased Enve Rims

Spotted: Frameworks Racing DH Bike with Electronic Fox Shock & Unreleased Enve Rims

A rare Spotted wombo combo.

Izzy Lidsky

Apr 20, 2024

Photo Report: Fun in the Sun at the 2024 Fuego XL

Photo Report: Fun in the Sun at the 2024 Fuego XL

The first in race in the Lifetime Grand Prix series set the tone for the North American off road season ahead.

Pinkbike Originals

Apr 20, 2024

Video: Prototype Suspension & New Modular Drivetrains From Sea Otter

Video: Prototype Suspension & New Modular Drivetrains From Sea Otter

Tune in for another day of Sea Otter.

Izzy Lidsky

Apr 20, 2024

Creatures of Sea Otter 2024

Creatures of Sea Otter 2024

From the makers of 'Tiny Dogs of Rampage' comes a new kind of anthropological study.

Mike Kazimer

Apr 19, 2024

Randoms Round 2: New Tools, Goggles, Grips, Racks, & More - Sea Otter 2024

Randoms Round 2: New Tools, Goggles, Grips, Racks, & More - Sea Otter 2024

Everything from extra-heavy-duty bikes racks to goggles designed for half shell helmets.

Archive Navigator

2024 Advertiser List

Brands

Bikes

- Trek

- Specialized

- Devinci

- Rocky Mountain

- Giant Bikes

- Scott

- Kona

- Norco

- Commencal

- NS Bikes

- Santa Cruz

- Yeti

- YT Industries

- Polygon Bikes

- Cube

- Radon Bikes

- Marin

- Guerrilla Gravity

- RSD Bikes

- Propain Bikes

- DMR Bikes

- Canyon

- PRIME Bicycles

- Pivot Cycles

Components

- SRAM

- Shimano

- Race Face

- Industry Nine

- SDG

- Deity

- Hunt Wheels

- One Up Components

- KS

- Rotor Bike Components

- Stan’s NoTubes

- Reverse Components

- RideWrap

- PROLOGO

- Yoshimura Cycling

- TRP Cycling

- Galfer USA

- Bikeyoke

- e*thirteen

- Geo Handguards

Suspension

Tires

Accessories

Coaching and Education

Online Retailers

Resorts/Riding

- Trestle Bike Park

- Bike Parks BC

- Fernie

- Crested Butte

- Big White

- Saalbach Hinterglemm

- Whitefish Mountain Resort

- Visit Tucson

- Monument Trails

- Mountain Bike Park City

Downhill Bikes of Sea Otter - Part 1

Downhill Bikes of Sea Otter - Part 1  What's New for the Kids at Sea Otter 2024

What's New for the Kids at Sea Otter 2024